I don’t steal other people’s books so much as ‘borrow’ them when they haven’t been officially lent to me. A primary instance happened when I was about eleven and my best friend and I were looking for trouble in her attic and found The Joy of Sex, a 1970s sex manual. We opened it up and simply stared. Body parts swelling and merging in ways we couldn’t imagine! And the man had long hair and a beard! This was mystifying in the age of Leo and the Backstreet Boys. We heard footsteps, and quickly stuffed the book back in its place, ensuring that the loose double-pages were folded back in. At that stage, we wanted a peek at knowledge that wasn’t available to us, but weren’t really ready to come to terms with it.

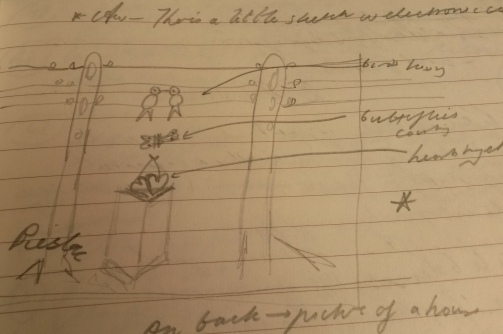

This summer, I was in the makeshift office that had once been my brother’s bedroom and spotted a tomato-red, twenty-fifth-anniversary edition of The Alchemist by Paulo Coehlo. I remembered my brother mentioning it before his motorcycle and bonobo monkey research trip around Africa, and was curious. On the inner leaf was a dedication from an unknown Nik to ‘Mowgli’, his explorer alter-ego:

I wasn’t on the African adventure, but wanted to identify with the ‘true warrior’ who would receive such a dedication, so I slipped the book into my bag. I didn’t feel too bad about it because my brother freely ‘borrows’ my books and returns them in the state of shipwrecked voyagers, with curled pages and half-eroded covers. Besides, he was out of reach, so there was no way to ask him for permission. The Alchemist, a story of a shepherd boy’s trek to Egypt in search of the pyramids and a promised treasure, accompanied me on my own journeys across London for the 5 days it took to read it. In Alan Clarke’s translation, Coehlo’s prose had the spare and sparkling quality of a fairytale, with a touch more sentiment.

Proverbial phrases from the sages the boy meets on his journey, jumped out at me. They seemed relevant beyond the novel’s concise 171 pages and made me feel that its quest was my own. This was Coehlo’s intention for the book and I took the bait. Here’s an assortment of proverbs:

1. ‘A blessing ignored becomes a curse…’ How simple, and yet how true. Neglected treasures, whether people, talents or possessions have a way of skulking around, casting great guilty shadows and becoming our enemies. A silk dress left in the closet attracts moths, a beloved who is taken for granted becomes a shrew, and creatives who sideline their practice are notorious drama queens and time-wasters.

2. ‘I know sheep can be friends… I don’t know if the desert can be a friend…’ This could be my favourite of the boy’s musings! It expresses gratitude and tenderness for the friendships he already has, and curiosity about the unknown. Sure, in many ways the arid desert seems the opposite of the shepherd’s fleecy flock; but he’s not about to dismiss it as an enemy out of hand. If more people were this open to difference, there would be less mistrust in the world and fewer wars, seriously.

3. ‘Love never keeps a man from pursuing his personal legend. If he abandons that pursuit, it’s because it wasn’t the love that speaks the language of the world…’ This comes up when the boy considers relinquishing his quest for treasure upon meeting Fatima, his heart’s desire, in an oasis. The statement advocates a world picture based on abundance and trust rather than scarcity and fear. It’s idealised, but I admire its generosity.

As much as The Alchemist paved its way into my thoughts, at times its gender bias reminded me that I had stolen the book from my brother. The male nameless shepherd’s personal legend is journey towards the treasure; whereas his Intended, Fatima’s personal legend is him. Fatima is given some of the most beautiful and moving lines in the book:

‘I’m a desert woman, and I’m proud of that. I want my husband to wander as free as the wind that shapes the dunes. And, if I have to, I will accept the fact that he has become a part of the clouds, and the animals, and the water of the desert…’

Her words are noble because they describe love as gift to be open to, but not as an entity that can be possessed and controlled. And yet, there is something limiting (Penelope-like) about her destiny as an eternally receptive vessel with no journey of her own. Doesn’t she want to wander too, have a personal quest that can coexist with her love, not be wholly informed by it? But there I go, imagining fairytale endings for a story that’s not mine…

Some borrowings require more tact and subtlety. Every Thursday I sit in my supervisor’s office for an hour, when students can come and ask questions about the course. They rarely do. So I sit on her spinning chair and scan shelf upon shelf of books. Some are gleaming and expensive, with the aura of gifts; others are tiny, rare and cloth-bound; these, I imagine, have been carefully sourced. Intriguingly specific studies of now-forgotten designers are juxtaposed with sentimental titles like Wartime Kiss and generic volumes from grand theorists. The books have been thematically arranged and delicately handled. Apart from the odd volume placed askew, perhaps as a reference point, they appear as untouched as Snow White under rock crystal. When I take one to pass the hour, because after all, no one said I shouldn’t, I’m careful not to touch the book too much, change its shape, or God forbid, break its spine, and replace it with the exactitude of evidence in a murder scene. In this space, bibliophilia means something different from my own cavalier love for my travelling volumes. As a thief of sorts, I must be respectful, or get caught.

Poaching books is a way of crossing each other’s boundaries. We do it because we’re curious and want to be close, perhaps as a way of identifying with someone, or gaining some sort of subtle knowledge about them, or for ourselves. It could be seen as a creepy act, because no-one has given you direct permission; but, done respectfully, it can also be an empathetic gesture. Perhaps a person’s books, like their actions and body language, are indirect or surrounding manifestations of their character and dreams, beyond the words they choose to speak. To adopt Coehlo’s theme, these unspoken signals form part of ‘the language of the world.’

Reading List

Alex Comfort, The Joy of Sex (London: Quartet Books, 1974). *

Paulo Coehlo, The Alchemist: 25th Anniversary Edition, trans. Alan Clarke (New York: Harper Collins, 2014).

Alexander Nemerov, Wartime Kiss (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

*I can’t remember which edition we found in the attic, but this is the original.